Wire Fracture – Miscellaneous – Case 2

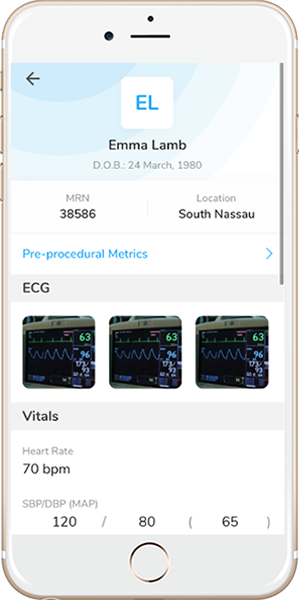

Clinical Presentation

- 77-year-old male who presented with chest pain (CCS Class 3).

Past Medical History

- HTN, HLD, DM, CAD s/p 3-Vessel CABG Followed by Multiple PCI’s, Asthma, Former Tobacco Use, COPD

- LVEF 60%

Clinical Variables

- N/A

Medications

- Home Medications: Aspirin, Clopidogrel, Atorvastatin, Metoprolol Tartrate, Ranolazine, Levothyroxine, Gabapentin, Cilostazol, Glipizide, Budesonide-formoterol, Montelukast

- Adjunct Pharmacotherapy: Clopidogrel, Bivalirudin

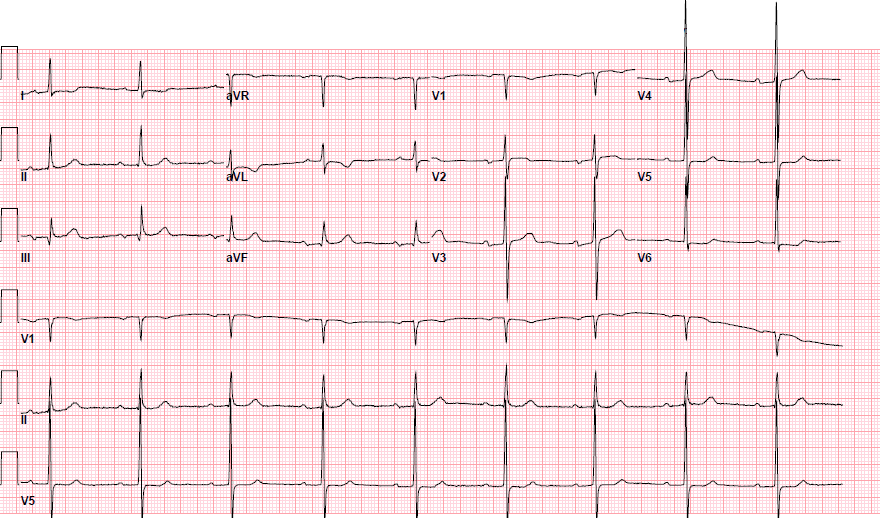

Pre-procedure EKG

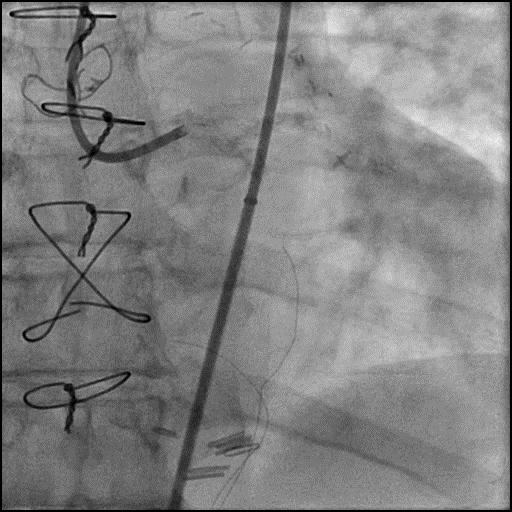

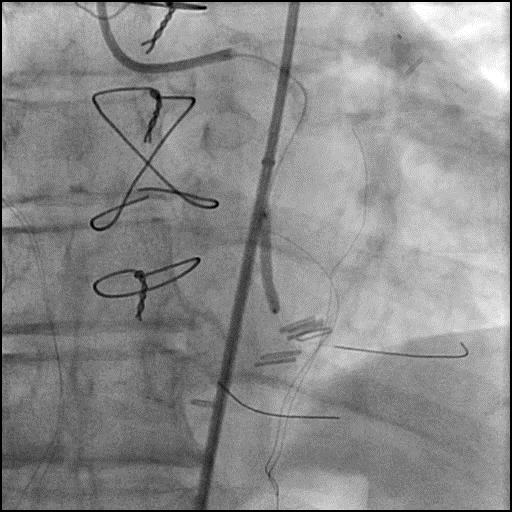

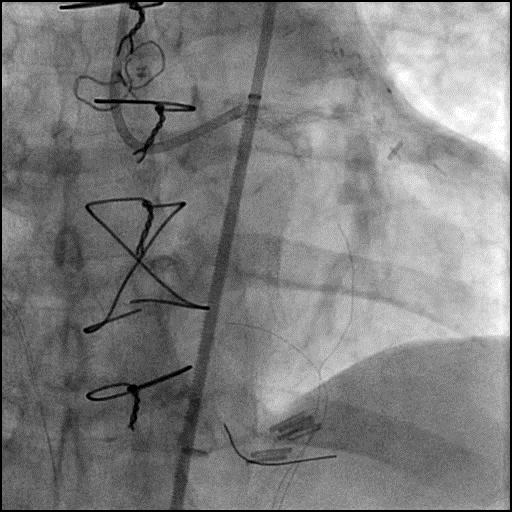

Angiograms

Previous

Next

1 of 6

Left coronary artery angiography

- patent intervention cite in the proximal left circumflex (LCx)

- 90-95% calcified lesion in the second obtuse marginal branch (OM2)

- subtotal calcified occlusion of the first left posterolateral branch (LPL1) and left posterior descending artery (LPDA).

Post-procedure EKG

Case Overview

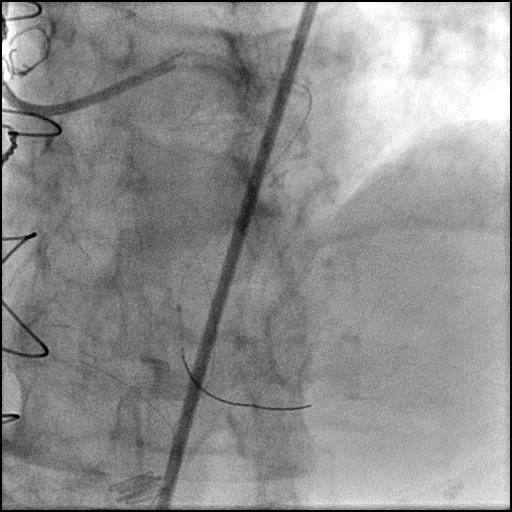

- Underwent intervention of the LPL1, and OM2 branch.

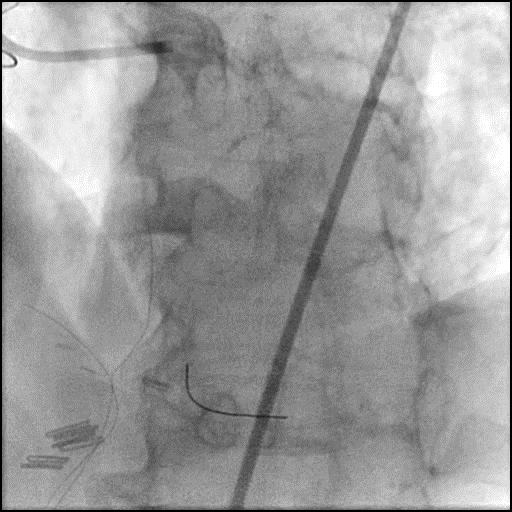

- While attempting intervention of the LPL1 the Fielder wire fractured following pre-dilatation of the lesion.

- Attempt to retrieve the remnant wire were abandoned as the wire was far distal in the LPL1 branch.

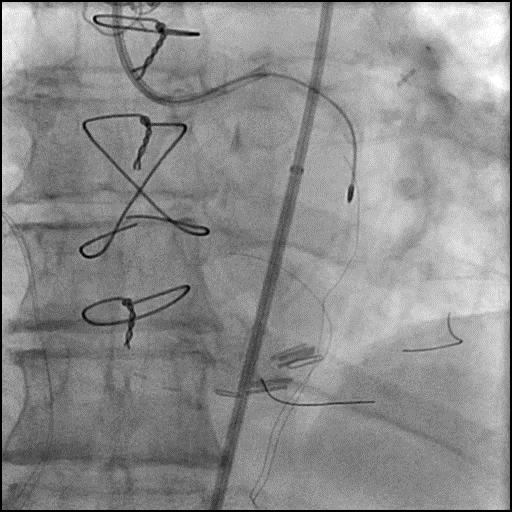

- The procedure was continued and successful intervention of the OM2 branch was performed.

- Troponin-I peaked at 0.4 ng/mL and CK-MB peaked at 3.2 ng/mL.

- Patient was discharged home next day without further sequelae.

Learning Objectives

- What is the likely explanation or reason why the complication occurred?

- PTCA of a subtotal occluded vessel with dense calcification likely resulted in the wire fracture at the soldered site of the wire.

- How could the complication have been prevented?

- Avoid performing PTCA with the balloon positioned over the soldered site of the wire.

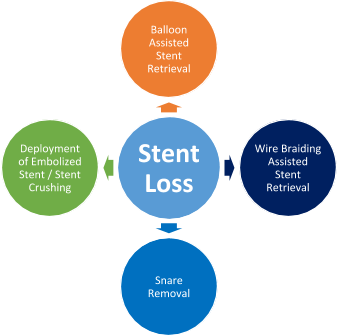

- Is there an alternate strategy that could have been used to manage the complication?

- Snare Technique: Retrieval of a lost/remnant guidewire is feasible with a GooseNeck snare or a Triple-Loop snare. It is usually easier to retrieve a fragmented/remnant guidewire if it is located proximally in a large coronary artery. Success also depends on an operators familiarity with use of the snare and ability to align the loop of the snare to the guidewire. When using a snare, need to make sure its length is longer than the length of the guide catheter being used.

- Multi-Wire Technique: Insert one or two coronary wires next to the remnant wire and twist the wires together so all wires become entangled, and can be removed together.

- Balloon-Trapping Guide-Extension Catheter Technique: A balloon is used to jail the remnant wire against the lumen of a guide catheter or guide-extension catheter.

- If a remnant wire is still within a guide catheter, retrieval using this method involves inserting another wire distal to the remnant wire, thread a balloon over it and inflate the balloon inside the guide catheter to entrap the wire between the inflated balloon and wall of the catheter, followed by removal of the entire system simultaneously.

- If the remnant wire is outside the guide catheter, insert a second wire distal to the remnant wire and use a guide extension catheter to get the proximal part of the fractured wire into the lumen of the guide extension catheter. If successful, deliver a balloon and inflate the balloon to trap the wire between the balloon and lumen of the extension catheter, followed by removal of the entire system simultaneously.

- Using a stent to plaster the wire should only be considered as a last resort, especially if the wire is located more proximally in a large caliber vessel.

- What are the important learning points?

- The weakest point of a wire is where the radio opaque and radiolucent part of the wire are soldered together, and performing an intervention across this segment of the wire should be avoided.

- When a wire is fractured within a coronary vessel, an attempt should be made to percutaneously retrieve the remnant wire or exclude it with a stent, particularly if the remnant wire is located proximal in a large caliber vessel. If the remnant wire is located more distal, it is reasonable to defer intervention. In this case, because the LPL1 branch was severely diseased and the wire was located distally within the vessel, attempts to retrieve it were deferred.