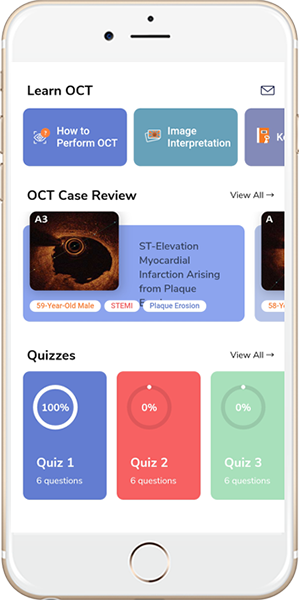

Air Embolism – Case 2

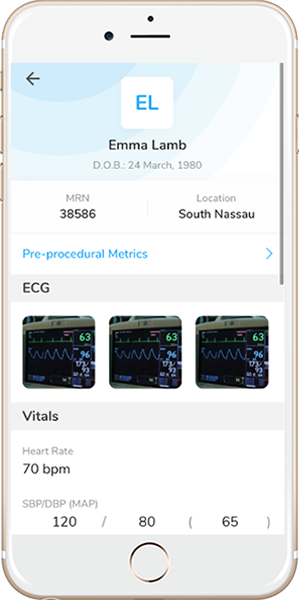

Clinical Presentation

- 59-year-old male who presented with chest pain (CCS Class III).

Past Medical History

- HTN, Active Tobacco Use

- LVEF 70%

Clinical Variables

- Stress MPI: Mild apical ischemia.

Medications

- Home Medications: Aspirin, Metoprolol Tartrate, Tamsulosin

- Adjunct Pharmacotherapy: None

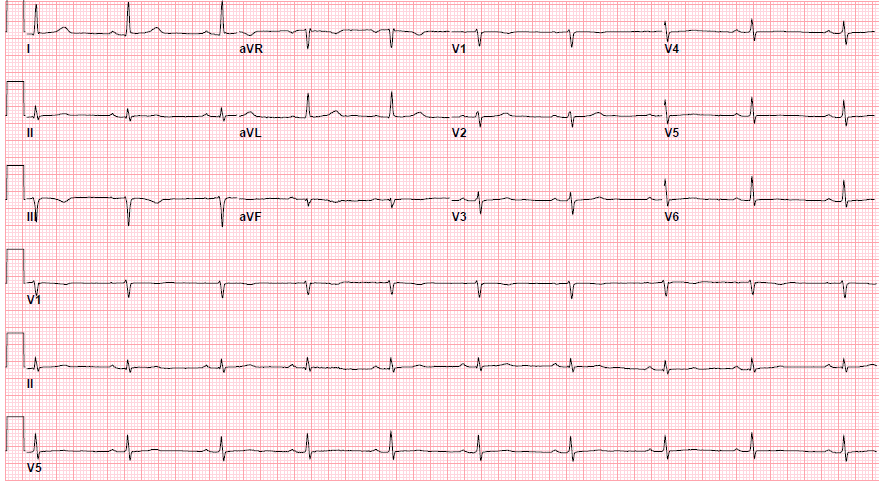

Pre-procedure EKG

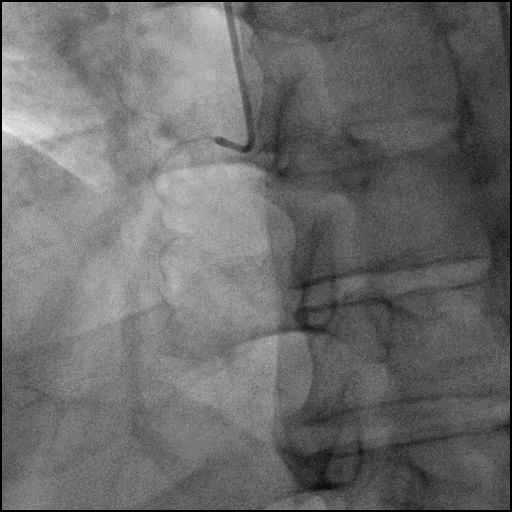

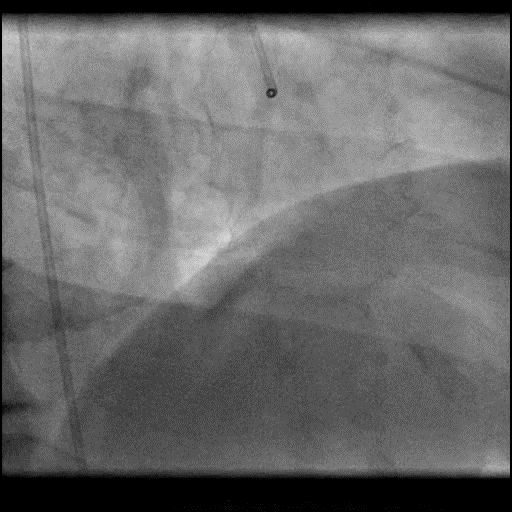

Angiograms

Case Overview

- Underwent diagnostic cardiac catheterization.

- Procedure was complicated by compromised flow of the RCA due to air embolism because of air within the manifold.

- Patient remained hemodynamically stable without significant EKG changes.

- Rapid aspiration and serial saline flushing was performed using the manifold followed by administration of IC vasodilators.

- Follow-up angiography of the RCA showed restoration of TIMI 3 flow without contrast dye ‘hang-up’.

- Troponin-I peaked at 0.0 ng/mL and CK-MB peaked at 0.8 ng/mL.

- Patient was discharged home the next day without any sequelae.

Learning Objectives

- What is the likely explanation or reason why the complication occurred?

- Air embolism due to inappropriate manifold preparation.

- How could the complication have been prevented?

- Proper preparation of the guide catheter and manifold.

- Do not engage the coronary ostium when you pull out the guiding wire unless the patient has excessive aortic tortuosity or an enlarged aortic root.

- Do not connect the manifold to the catheter with the flush running. This may lead to an air embolism if the catheter has a column of air already in it.

- It is essential to properly prepare and de-air all catheters, especially diagnostic/guide catheter prior to connecting them with the manifold:

- Draw back at least 2 ml of continuous blood into the injection syringe, which should be filling with saline. If you see a large amount of air in addition to blood being drawn back, pull back the catheter until there is only free flowing blood being drawn back.

- Discard the saline/blood mixture into the one-way waste bag. Draw back saline and discard into the waste bag until there is no air in the system.

- Draw back dye into the syrine for injection.

- Attempt to inject a few ml of dye into the ascending aorta before engaging the coronary ostium.

- Once engaged, continue with cine acquisition and angiography by injecting contrast.

- Proper handling of the manifold to prevent inadvertent air injection.

- Hold the manifold at 45° and assure no air is within the syringe prior to injecting.

- Never fully inject all the contents within the 10 cc syringe (leave 1-2cc).

- If there are minimal air bubbles with in the syringe, gently tap the syringe to allow them to ascend to the top.

- If air is in the manifold, disconnect the syringe from the manifold and empty it, back flush the manifold with saline continuously flushing and then reconnect the syringe to the manifold.

- Pay attention to the entire system (tubing, contrast bottle etc.) to assure no air is within the circuit.

- Is there an alternate strategy that could have been used to manage the complication?

- There are various management strategies aimed at restoring blood flow in the affected coronary and depend on the patients hemodynamic status, and include the following:

- 1st: Vigorous saline flush into the coronary arteries and aspirate blood via guide catheter and inject forcefully back into the coronary artery.

- Assure catheterization system is air tight and allow bleed-back from the catheter to clear any residual air in the system prior to performing this.

- Air aspiration should be performed quickly using the catheter which is already being used to cannulate the vessel (diagnostic catheter, guide catheter or thrombectomy catheter etc.).

- 2nd: Hemodynamic support to increase perfusion pressure to assure adequate coronary perfusion.

- Blood pressure management:

- If hypotension and SBP is 50-90 mmHg give IV phenylnephrine 200 ug push and followed by flush with saline, repeat as needed every minute

- If blood pressure is non-measureable give IV epinephrine 1cc of [1:10,000 dilution] push and followed by flush with saline, repeat as needed every 2 minutes

- Bradycardia Management:

- IV atropine 0.5-1mg (up to a dose of 3mg), Dopamine 2-10 ug/kg/min gtt, and/or epinephrine 2-10 ug/min gtt

- Transcutaneous pacing or temporary venous pacer

- 3rd: Dissolving or passage of the air embolism by transient elevation of intra-atrial pressure by use of inotropes and intra-aortic balloon pump.

- 4th: 100% oxygen to promote nitrogen diffusion.

- 5th: Use of vasodilators (adenosine, CCB, nitrates) for treatment of slow flow/no-reflow.

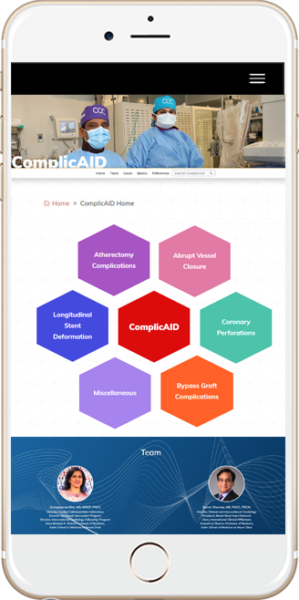

- What are the important learning points?

- Air embolism is almost always iatrogenic and may result from inadequately flushed catheters, introduction or withdrawal of balloon catheters and guidewires, rupture of the balloon, defective manifold systems, leaky equipment.

- Air embolism can cause acute chest pain, loss of consciousness, hypotension, arrhythmias, bradycardia, conduction blocks, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (most common EKG finding), discreet vessel cutoff (most common angiographic finding), slow flow/no-reflow phenomenon, and death.

- Signs and symptoms are dependent on the amount of air introduced into the coronaries, number of vessels affected, baseline cardiac function) and vascular response to symptoms.

- Guidelines for management of coronary air embolism are lacking. Emphasis should be on prevention by thoroughly flushing cardiac catheterization equipment and carefully aspirating the catheters. Early recognition is very important. In this case we noted dye ‘hang-up’ in the RCA, raising our suspicion for coronary air embolism. When suspicion for coronary air embolism is high or confirmed NO FURTHER angiographic images should be acquired.