Perforation Type 2 Wire – Case 4

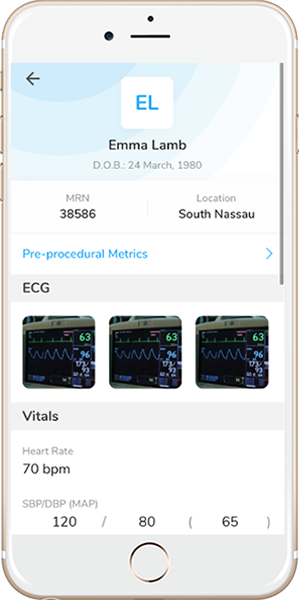

Clinical Presentation

- 76-year-old female who presented with chest pain (CCS Class III).

Past Medical History

- HTN, HLD, CAD s/p PCI, CVA

- LVEF 60%

Clinical Variables

- Stress MPI: Mild to moderate size inferior perfusion defect.

Medications Heading

- Home Medications: Aspirin, Ticagrelor, Atorvastatin, Metoprolol Tartrate, Amlodipine, Diazepam

- Adjunct Pharmacotherapy: Ticagrelor, Bivalirudin

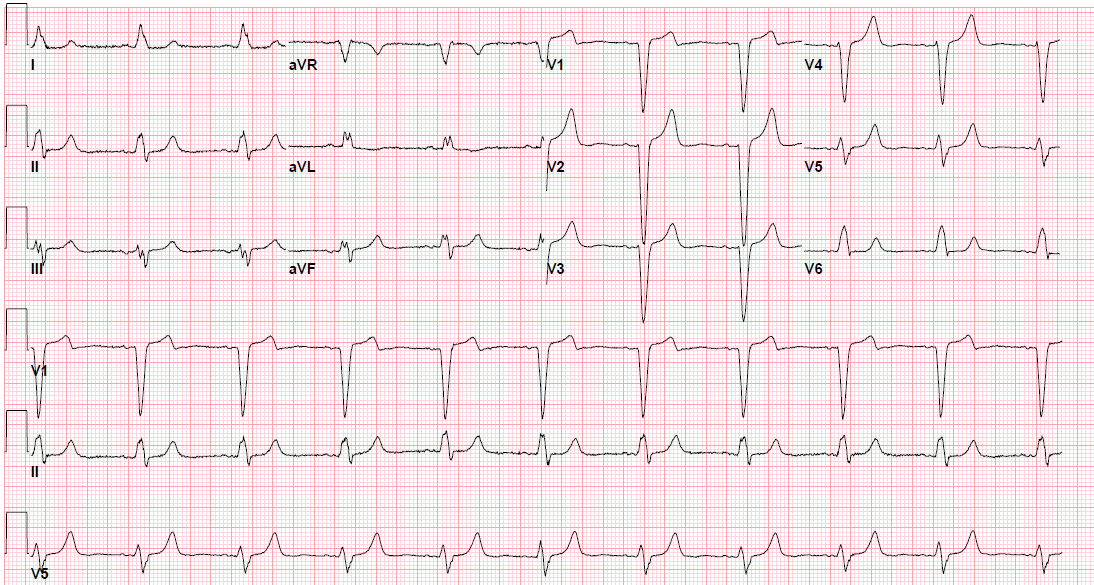

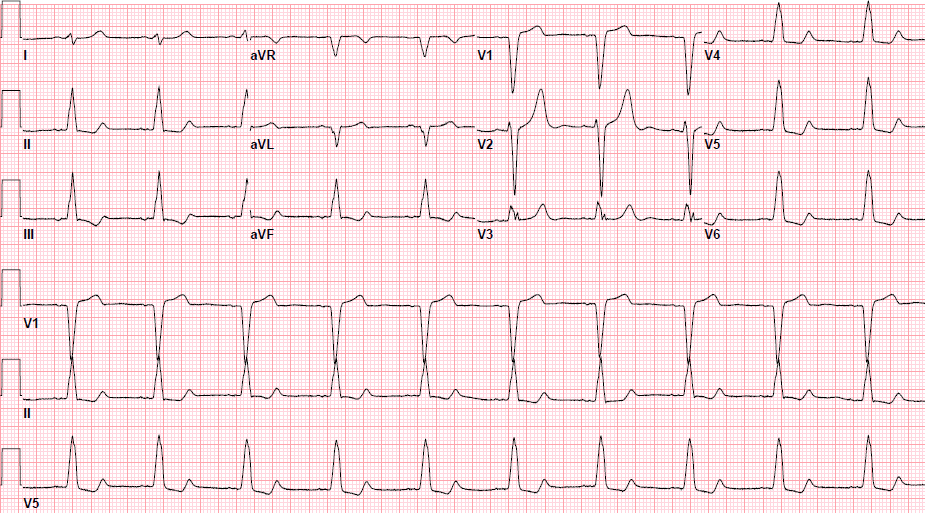

Pre-procedure EKG Heading

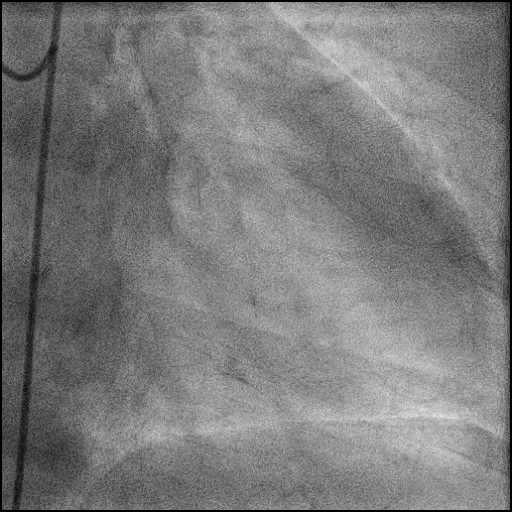

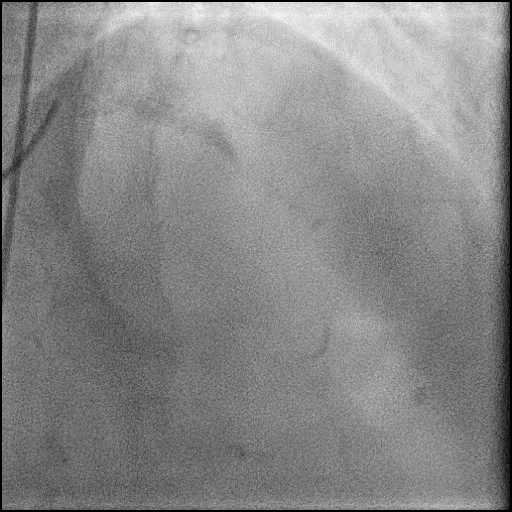

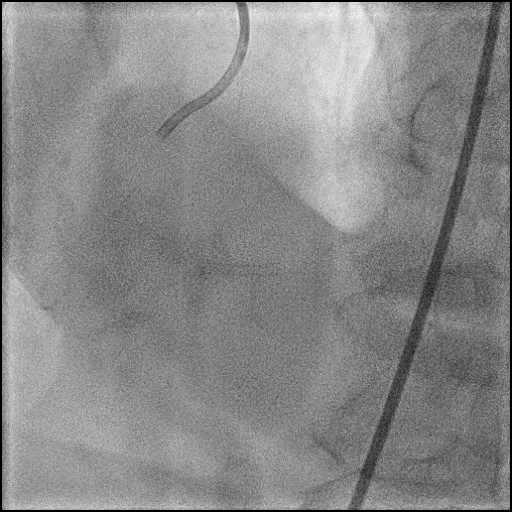

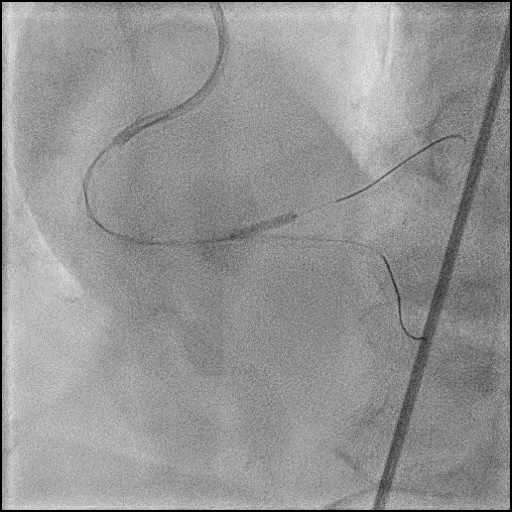

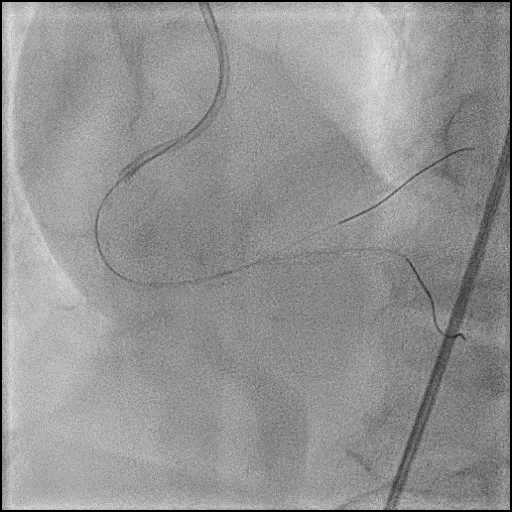

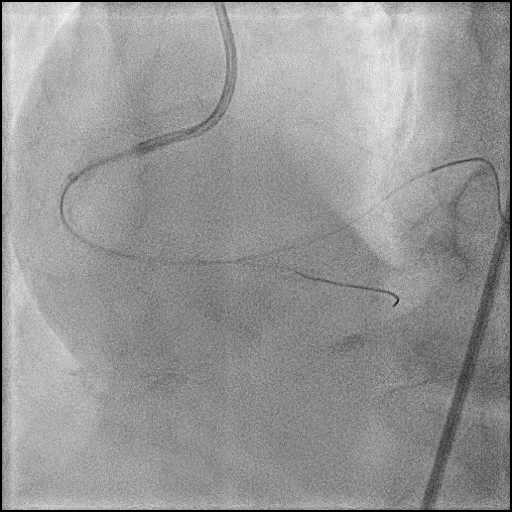

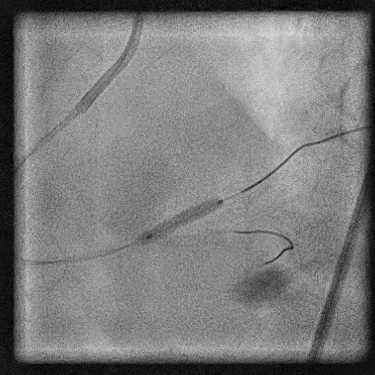

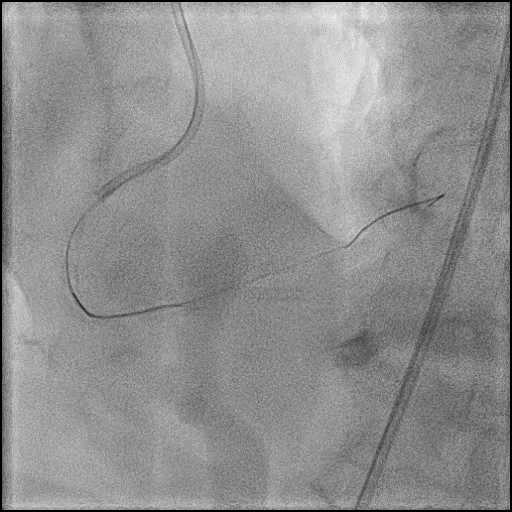

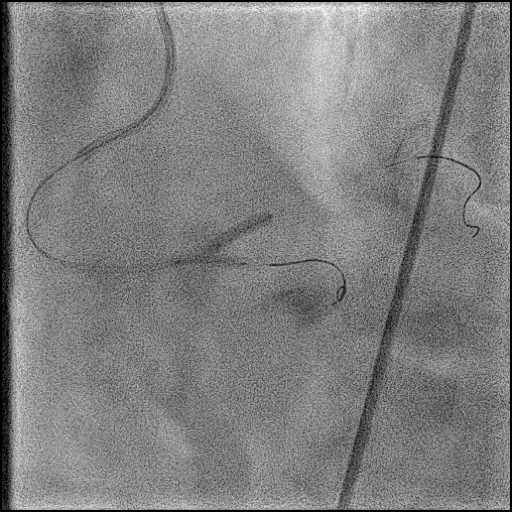

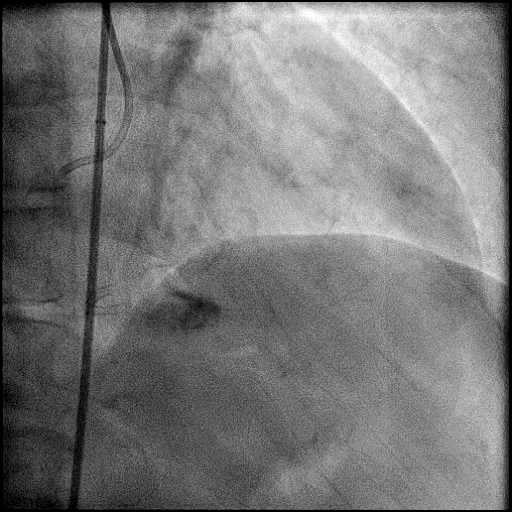

Angiograms

Post-procedure EKG

Post-procedure Echocardiography

Case Overview

- Underwent intervention of a the AV-Continuation.

- Procedure was complicated by a type 3 distal wire perforation involving the RPDA which was sealed with prolonged balloon tamponade of the vessel.

- Echocardiography showed presence of a trace pericardial effusion without tamponade physiology.

- Troponin-I peaked at 3.48 ng/mL and CK-MB peaked at 18.9 ng/mL.

- Patient discharged home three days later without any sequelae.

Learning Objectives

- What is the likely explanation or reason why the complication occurred?

- Wire related perforation (Around 50% of coronary perforations are guide wire related).

- How could the complication have been prevented?

- Careful manipulation of the wire. Ideally, a wire should be positioned distal to a lesion in a large caliber vessel so long as it provides sufficient support to perform a coronary intervention.

- Extreme caution needs to be taken when using a hydrophilic wire (i.e. Fielder, Whisper wires etc.). Hydrophilic wires are more prone to cause a perforation as they tend to navigate into smaller branch vessels and provide less tactile feedback.

- Using a workhorse, non-hydrophilic wire with tip load <1g when performing a coronary intervention helps reduce complications.

- Is there an alternate strategy that could have been used to manage the complication?

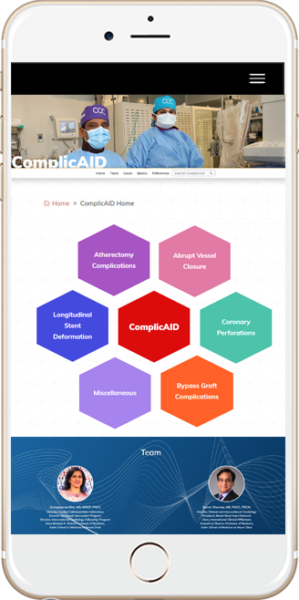

- Ellis Type 1 and 2 perforations usually seal spontaneously and are conservatively managed. Such patients should be closely monitored in the catheterization lab, and serial echocardiography should be performed, particularly if there is an Ellis Type 2 coronary perforation because it may lead to cardiac tamponade. Ellis Type 3 perforations are associated with increased risk of cardiac tamponade and mortality, and require immediate intervention/treatment. Ellis Type 3 Cavity Spilling perforation management is unclear. Usually, they are conservatively managed, unless there is significant extravasation or the patient is symptomatic.

- Coronary perforation management algorithm:

- 1st: Prolonged balloon inflation: Position the balloon (or stent-balloon post stent deployment) just proximal or at the level of the perforation to prevent ongoing extravasation and development of hemo-pericardium. Ideally, the balloon to artery ratio should be 1:1. Inflate for 5-10 minutes followed by test deflations with contrast given in between inflations to evaluate the status of the perforation. If there is ongoing extravasation, re-inflate the balloon to stop further extravasation of blood into the pericardial space. This strategy helps stabilize the patients and gain control of the situation, while the operator prepares for echocardiography, pericardiocentesis, and more definitive treatment to seal the perforation.

- 2nd: Anticoagulation management: ‘STOP’ all anticoagulation immediately if you suspect or visualize a perforation. We consider ‘REVERSING’ heparin with protamine sulfate (to achieve ACT <225s) after coronary equipment is removed to prevent thrombosis within the vessel. If using bivalirudin, it can take up to 1-2 hours for its anticoagulation effect to a normalize after it is stopped. If patient was on glycoprotein IIB/IIIA inhibitors: For abciximab, consider giving platelet transfusion; tirofiban and eptifibatide have a short half life and their reversal can typically be achieved by stopping there infusion or in extreme cases with hemodialysis. Cangrelor has a short half life and its reversal can be achieved by stopping its infusion.

- 3rd: Covered stent: Standard of care for a perforation located in the proximal to mid segment of a vessel of appropriate size (≥2.5 mm), with no major side branch across the region where the stent will be placed. If a covered stent can be delivered to a distal vessel perforation, and the vessel is of appropriate size, covered stent placement to seal the perforation is reasonable. If the clinical situation allows, proceed with direct stent placement whenever possible using a single catheter or two-catheter (Ping-Pong) strategy. The stent should be quickly positioned and immediately deployed to high pressure. This should be followed by high pressure post-dilatation (18-20 atm) to achieve appropriate stent apposition.

- 4th: Embolization of distal vessel perforations: Non-surgical techniques for distal vessel embolization include: Coils, Gel Foams, Glues, Microspheres, Thrombin injection, Subcutaneous tissue, Autologous Blood Clots and multiple other agents (depending on what is available in an individual catheterization lab). Embolization leads to loss of vessel flow beyond point where embolized material is delivered and subsequent infarct in the vessel territory.

- 5th: Surgery Intervention: Ligation or suturing of the vessel for hemostasis with bypass grafting to the distal vessel. Pericardial patch/Teflon with possible bypass grafting to the distal vessel (consider this approach if vessel has multiple stents and/or presence of a subepicardial hematoma).

- What are the important learning points?

- When a complication occurs, an operator needs to quickly recognize and assess the situation to see if treatment of the complication should take precedence.

- In this case, the actively extravasating perforation should have been treated before intervention of the AVC, as this patient could have developed cardiac tamponade. One of the management strategies in treating coronary perforation involves stopping anticoagulation therapy. If a stent is placed prior to treatment of a perforation, the reversal of anticoagulation could lead to a catastrophic event such as acute stent thrombosis.