Vasospasm – Case 2

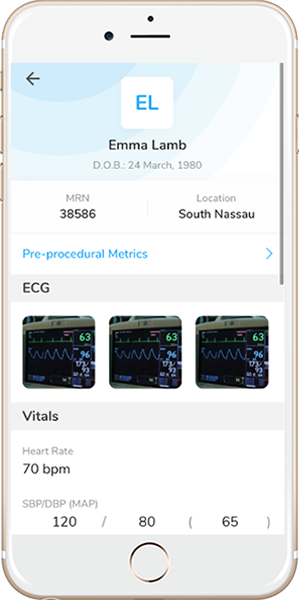

Clinical Presentation

- 61-year-old female who presented with a NSTEMI.

Past Medical History

- HTN, HLD, GERD, Depression

Clinical Variables

- Echocardiography: Global Hypokinesis, LVEF 45-50%.

Medications

- Home Medications: Aspirin, Atorvastatin, Nifedipine, Hydrochlorothiazide, Omeprazole, Albuterol, Venlafaxine, Sertraline

- Adjunct Pharmacotherapy: Clopidogrel, Bivalirudin

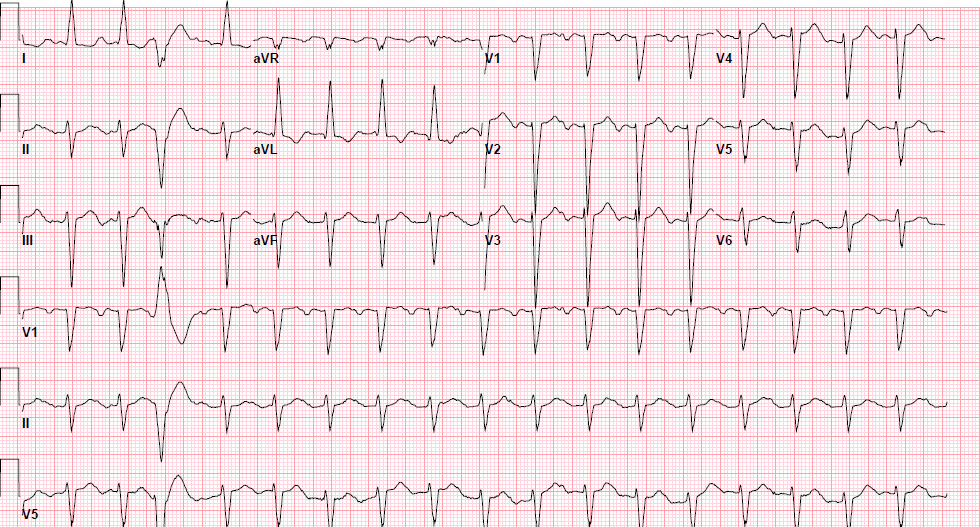

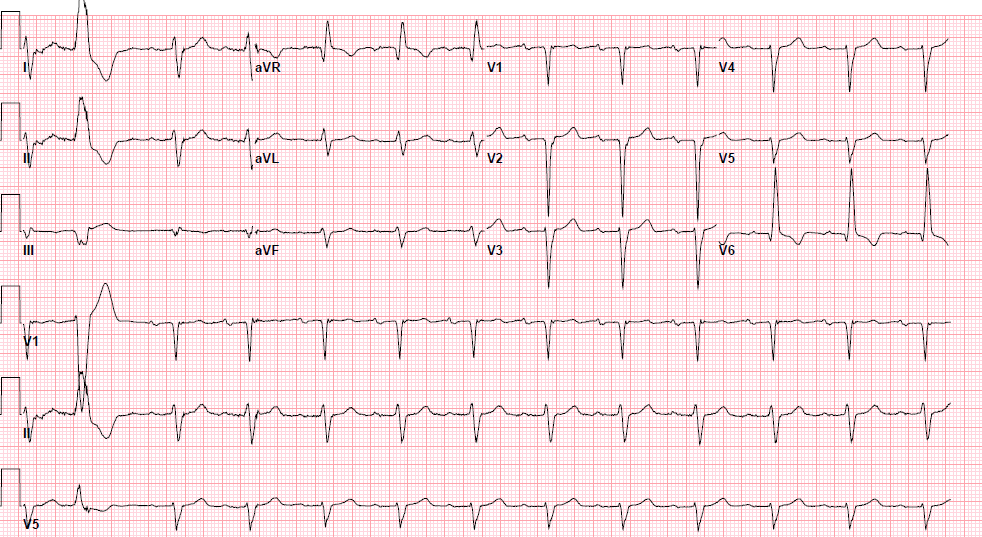

Pre-procedure EKG

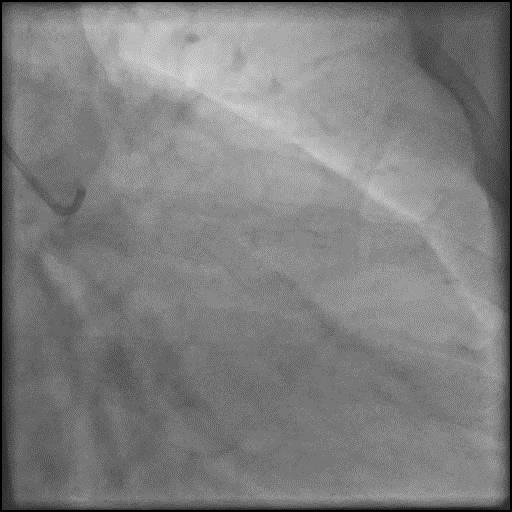

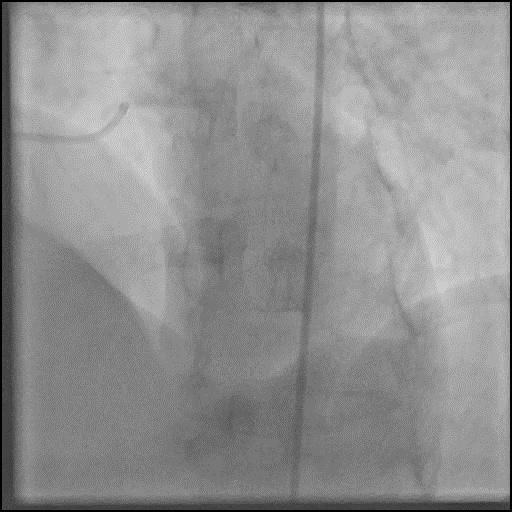

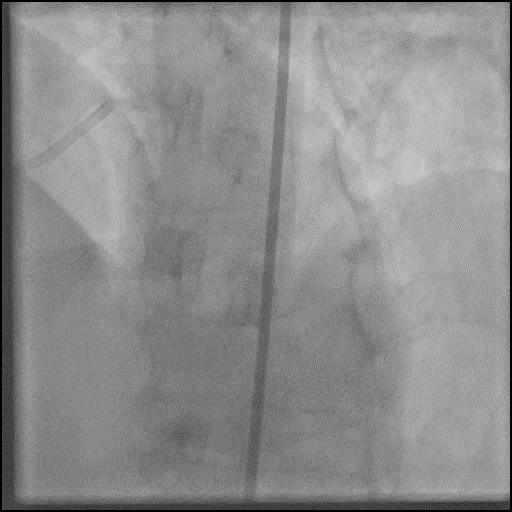

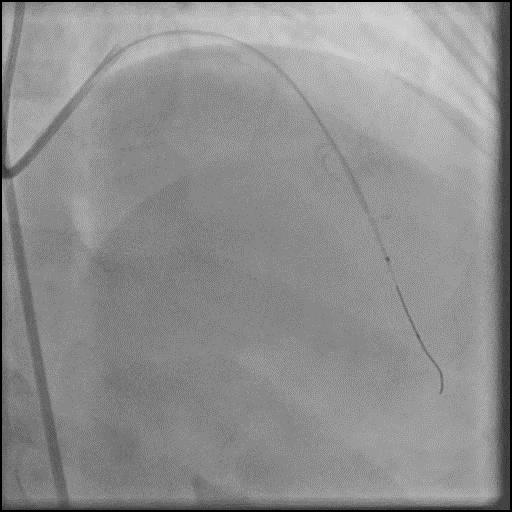

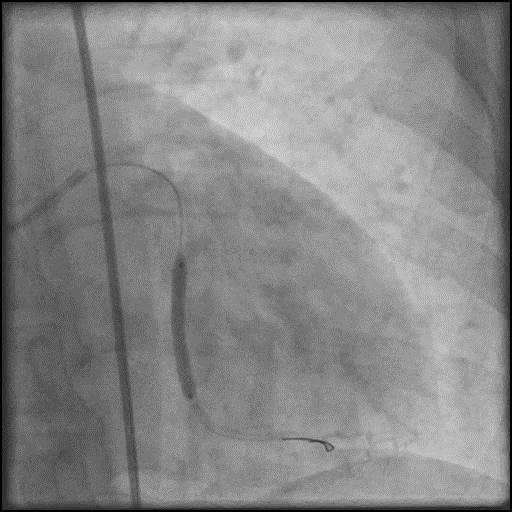

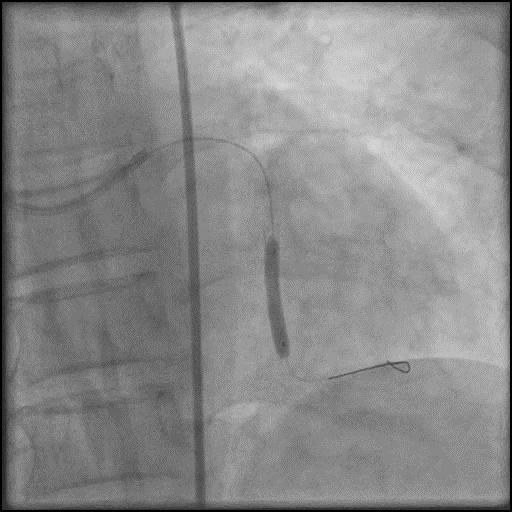

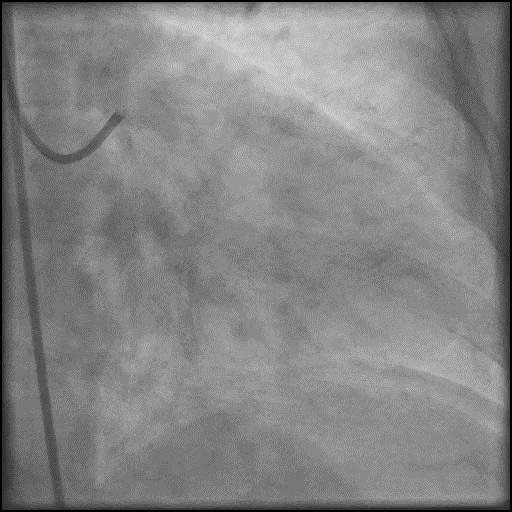

Angiograms

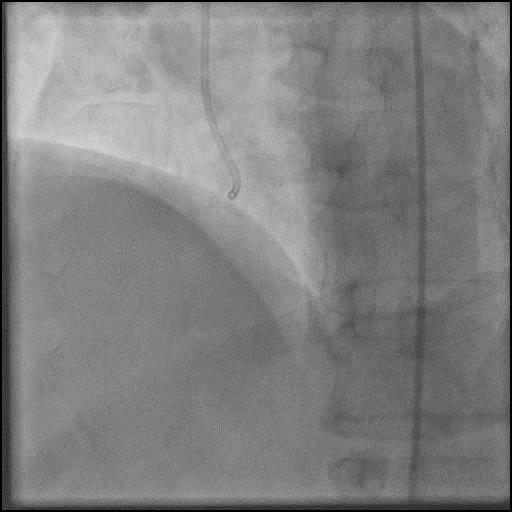

Post-procedure EKG

Case Overview

- Underwent intervention of LCx.

- While performing LCA angiography, a focal lesion was seen in the LAD.

- IC vasodilators were given and lesion resolved, confirming coronary spasm.

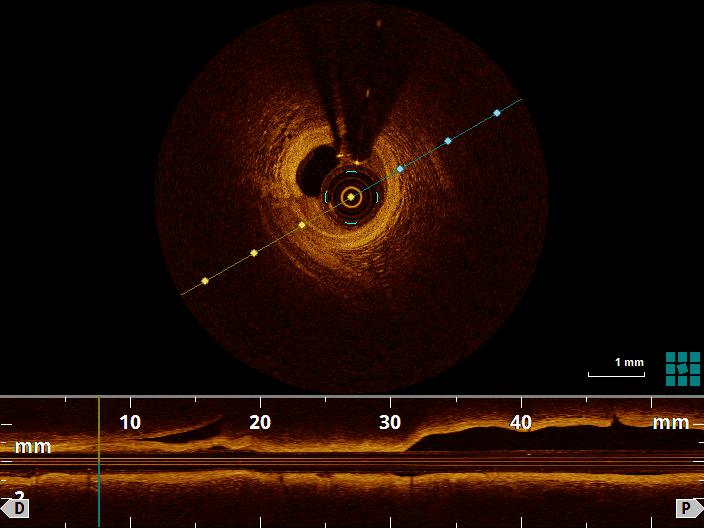

- OCT imaging was performed confirming absence of plaque within the LAD at the location of the focal defect.

- Troponin-I peaked at 19.1 ng/mL and CK-MB peaked at 147 ng/mL.

- Patient was discharged home the next day without further sequelae.

Learning Objectives

- What is the likely explanation or reason why the complication occurred?

- Coronary Spasm: the most common cause of intra-procedure coronary spasm is guidewire or balloon/stent manipulation. Catheter-induced spasm which usually involves the RCA ostium more often than the LCA ostium, and typically is within 2cm of the catheter tip. Cases where rotational atherectomy is used are more prone to coronary spasm. Coronary spasm occurs because of endothelial denudation and nitric oxide loss.

- How could the complication have been prevented?

- Vasodilators should be given prophylactically and for treatment of coronary spasm, especially when performing ostial RCA and LCA interventions.

- Is there an alternate strategy that could have been used to manage the complication?

- Step by step algorithm for management of coronary spasm:

- 1st: Intra-coronary/intra-graft vasodilators should be given slowly through a catheter, especially if using a guide catheter with side holes to maximize delivery into the artery. If one agent is unsuccessful, give combined therapy as CCB and nitrates have additive effect. We use the following agents and administer them intra-coronary/intra-graft:

- Nitroglycerin 100-200 mcg, Verapamil 100-200 mcg, Nicardipine 100-200 mcg

- 2nd: If medical therapy fails, remove hardware without losing coronary guidewire position to minimize mechanical provocation

- 3rd: If persists, consider performing prolonged (2-5 min) PTCA at low pressure (1-4 atm).

- 4th: In rare cases, a stent can be placed if above measures fail. Placement of a stent should be avoided as much as possible because it may propagate the spasm in either direction of the stent. Remember, refractory spasm may be indicative of dissection, which is also treated with a stent.

- Intra-coronary/intra-graft imaging with IVUS/OCT may be used to help elucidate the etiology of a focal lesion.

- What are the important learning points?

- If a new lesion appears while performing a procedure an operator has to consider a broad differential which includes coronary spasm, thrombus, dissection, plaque shift, and pseudo-stenosis.

- Coronary spasm is classified as:

- Focal coronary spasm: involves a single localized segment of a single coronary artery

- Multifocal coronary spasm: involves multiple localized segments of the same coronary artery

- Multivessel coronary spasm: involves segment(s) of more than one coronary artery

- Coronary spasm may appear benign but can lead to life-threatening arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities. Prognosis is worse in patients who have combined CAD and coronary spasm.

- Definitive diagnosis of coronary spasm is made angiographically when there is a luminal narrowing in a segment of a vessel that is shown to be reversible, typically with administration of intracoronary vasodilators.

- If there is a new focal defect(s) after introduction of coronary equipment, remember to review the initial acquisitions and follow the algorithm as detailed above. Often times both a spasm and pseudo-stenosis can present simultaneously, and both IC vasodilators and removal of coronary equipment is necessary for the filling defect to resolve. However, if there is concern for dissection or thrombus, wire position should NOT be lost.